For Congregation Ner Shalom ~ March 1, 2013

It’s spring up on Sonoma Mountain. I’m able to witness this rebirth every day as I drive up and down. The grass is dazzling green. The Sonoma State students are trying out Gravity Hill by day and making out in their cars by night. Much of my route is grazing land and every cow on the Mountain now has a calf at her side. And those calves are fearless – they will stand in the road and stare you down. And they are furry. And frisky. They scamper like lambs. Oren and I saw a calf chasing a snowy egret in a field just to make it fly, like Ari used to do with pigeons when he was little. Chasing birds just for the fun and wonder and power of it. As if saying, “Look! I run like the wind!” These calves on the Mountain are full of frolic even though we know they will end up as heavy-footed ruminators, eventually taking a full day for a single patch of grass or for a single thought; although who knows? Maybe they’re still impulsive and bouncy on the inside.

So yes, calves are delightful.

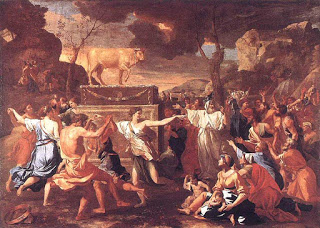

Unless they are forged of gold and danced around by Israelites.

Because here we are this week, once again reading the old story. About how Moshe goes up the Mountain to receive the law and is gone for 40 days while God gives over not only laws of conduct but instructions for the architecture and appointment of the ark and the tabernacle that will hold it; the mishkan, the holy Tent of Meeting that will be the place, says God, where God and the Children of Israel will meet. But meanwhile, in the valley, the Children of Israel also want to meet the divine and, giving Moshe up for lost, they demand a god now. Aaron asks them for all their gold, maybe thinking that such a high price tag would sober them up. But they are generous; they in fact give it all up, because they want god that badly. They give their most precious things, the very items that capital-G God was busy commanding them to incorporate into the decoration of the mishkan.

The Children of Israel dance around their new creation, and sing, “This is your God, O Israel, who led you out of Egypt.” God is furious. Moshe calms God, but takes his turn to be angry as he descends the Mountain and sees the spectacle. The Children of Israel are punished for their act of idolatry or infidelity.

I never know what to do with this text. I’m not very good with simple right and wrong lessons, especially in matters of the spirit. I don’t like being told there’s a right way and a wrong way, and that the wrong way leads to punishment. This is why I belong to a community like this one and not to communities that are more unyielding in their view of how things should be done.

I can’t help but feel sympathetic to the Israelites, because the wrongness of what they did is not completely obvious, at least not to me. We know from Torah that they will soon be crafting things of great beauty to facilitate the human-divine encounter in the mishkan. Altars of wood and hide, with gold and silver and jewels. And statues of cherubim, too. So it’s not exactly the making of images that’s the problem here, because images are about to be made at God’s own request. We also know from God’s words to Moshe up on the Mountain that there are many skilled people among the Israelites, gifted by God with tremendous creative talent and filled with God’s spirit. Wouldn’t art-making as an approach to the Divine be a natural impulse for them?

I’ll defend them even more. There they were, the Israelites, in the Wilderness, a place with no landmarks, with no certainty. Might it not be a tough time to absorb the idea of a God that is also without landmarks, without physical certainty? They knew from Egypt that you represent gods symbolically through animals; seeing the unknown through the known; they knew the goddess Hathor was commonly rendered in the form of a cow. And for this new god, this upstart who impulsively took them out of slavery? What better image than a calf? Powerful and a future source of nourishment like Hathor, but still young and fierce and nimble like the calves on Sonoma Mountain!

The calf wasn’t a denial of God. At least maybe not. The people were certainly doubting Moshe’s return. But were they really doubting the existence of the God of Israel? They’d seen the Waters part. They’d seen the pillar of smoke by day and column of fire by night. They’d heard the thunder on the Mountain. Their daily diet was manna from heaven. No, I don’t think this was an act of rejection of Adonai, but of worship. They were just using the vocabulary they knew for it. I don’t know about you, but I remain sympathetic.

Their crime, if there was one, was not idolatry, but impatience, impulsiveness. They wanted a fast hit of ecstasy, and they got it. We see it in their euphoric singing and dancing around the calf.

Whereas, in contrast, the kind of worship God was asking for, the instructions for which had not yet actually reached the ears of the Israelites, involved something more time-consuming and deliberate. The Tent of Meeting, that is the tent where God and the people would meet, was something to be constructed with painstaking detail and tended with constant attention. Lights to be lit at proper times. Concocting the right incense, and burning it, and only it, twice a day. Sacrificing the right creatures in the right season; their blood to be sprinkled exactly the same way every time.

In the ritual world God wants, there is no quick fix. There is only practice, repetition, discipline, the consequence of which is, in God’s words, “There I will meet you and there I will speak to you.”

God seems to want closeness, but wants that closeness to come out of deliberateness, mindfulness, practice, actions, even seemingly small actions. But what of the ecstatic moment? Isn’t that remarkable also? Doesn’t it excite us and entice us too? Haven’t we experienced moments like that? Are those, in our tradition, simply valueless?

Maybe not. I recently read a beautiful teaching of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Chasidism, and certainly no stranger to euphoric moments and ecstatic practice. In this teaching, the Baal Shem addresses the question of what happens when you have a mind-blowing God experience. Where your consciousness, your sechel, splits open and you have a glimpse of God’s unity and oneness and all-encompassingness, and it inspires you to this great love and devotion, because you’re grokking, really grokking a piece of God’s greatness. And this lasts for a brilliant moment – or a few. And then – poof – it’s gone. Your sechel is closed up again, and you don’t understand any of it. “What is that experience,” asks the Baal Shem.

So he explains by making a comparison to a shopkeeper in the market place. The shopkeeper sells sweets, and he markets them by giving out free samples. Think of See’s Candy or any Cape Cod fudge emporium. This first piece is free. And that first piece is also the last piece that is free. After that, the customer has to pay for it – with money that comes from and represents her labor. So the second encounter, the transaction for the second piece of fudge, is not something for nothing, but is a real exchange of value.

The Baal Shem Tov says that the brief moment of enlightenment, of God-awareness, is a free sample given milam’alah – from above. It is God’s free sample, and it is, in the words of Psalm 19, “sweeter than honey and the honeycomb.”

But after that first taste, we can only re-attain the experience milamatah – from below. Through our own labor: our study, our ritual, our practice.

“No pain, no gain,” says the Baal Shem Tov. When someone has attained their enlightenment through yegi’ah, or long, hard labor, their insights deserve to be believed. Just as we’d believe the insights of a longtime practicing Buddhist over an enthusiast just back from their first Vipassana retreat. Because we know the longtime practitioner has gone and meditated over years of cold mornings when she would have preferred to stay in bed. When she says this is worthwhile, it carries weight.

So the message seems to be that the God-hit is delicious, but it’s just a sample. From there it’s up to us. To establish a practice, maybe (hopefully) a Jewish practice, whatever that might be. I’d suggest it should be something inconvenient. Something tied to time. Unplugging your computer for Shabbat. Coming to chant circle not once in a while but every month. Committing to learning, as many Ner Shalomers have been doing through our Hebrew class or the countywide Introduction to Judaism class. Or committing to deepening your understanding of our forms of worship, as many Ner Shalomers have done by stepping up to lead services when I’m on the road. Or committing to an adult Bar or Bat Mitzvah track, as more than a half-dozen people in this congregation have just done. Or even committing to a regular personal practice of mindfulness and gratitude, maybe through learning Hebrew blessings for every occasion.

The Baal Shem Tov says, and I fear it’s true, that there is no substitute for hard work. There is no shortcut to the enlightenment, no matter how much pot you smoke or Ayahuasca you ingest. Sensing your Oneness with the Universe, meeting God at the Tent of Meeting, comes from experience, not accident. It comes with practice, not chance.

This isn’t an argument against improvising, chas v’chalilah. Improvisation is one of the things we do so well here at Ner Shalom. And, as you know, in my other life, my performing life, my skill as an improviser has specific value. But my best improvisations may come in the moment, but they draw from years of experience. I may blurt them out quickly, but I generally already know that they’re going to work. And the best improvisations? I repeat them, and they become tradition.

There are many ways – new, improvised ways as well as the age-old paths – to reach the mishkan, the holy place. But if you ask the question, “How do I get there,” the answer will likely be, as in the old joke, “Practice.”

So let us keep practicing and keep improvising – as a community and as individuals. May our improvisations come from an ever-deepening understanding of our lives and our tradition. May our learning be regular and may it fuel our creativity. And may the gold that is in our spirits adorn the place where we and God meet.